- Home

- S. P. Tenhoff

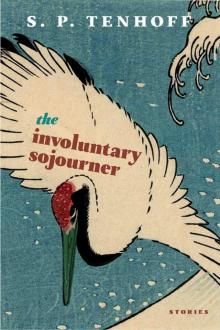

The Involuntary Sojourner

The Involuntary Sojourner Read online

the

involuntary

sojourner

STORIES

S. P. TENHOFF

Seven Stories Press

New York • Oakland • London

Copyright © 2019 by S. P. Tenhoff

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Seven Stories Press

140 Watts Street

New York, NY 10013

http://www.sevenstories.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Tenhoff, S. P., author.

Title: The involuntary sojourner : stories / S.P. Tenhoff.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019023453 (print) | LCCN 2019023454 (ebook) | ISBN

9781609809645 (paperback) | ISBN 9781609809652 (ebk)

Classification: LCC PS3620.E546 A6 2019 (print) | LCC PS3620.E546 (ebook)

| DDC 813/.6--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019023453

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019023454

College professors and high school and middle school teachers can order free examination copies of Seven Stories Press titles. To order, visit www.sevenstories.com, or send fax on school letterhead to 212-226-1411.

Printed in the USA.

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The following stories previously appeared, sometimes in slightly different form, in the following publications: “Ten Views of the Border,” American Short Fiction; “Maseru Casaba 9,” The Antioch Review; “Liability,” Swink and Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading; “The Visitors,” The Gettysburg Review; “Winter Crane,” Fiction International; “Diorama: Retirement Party, White Plains, 1997,” Conjunctions; “Ichiban,” Confrontation and Sequestrum; “The Book of Explorers” and “Kurobe and the Secrets of Puppetry,” The Southern Review; “The Involuntary Sojourner: A Case Study,” Conjunctions’ online magazine.

For W.

Contents

Ten Views of the Border

Maseru Casaba 9

Liability

The Visitors

Winter Crane

Diorama: Retirement Party, White Plains, 1997

Ichiban

The Book of Explorers

Kurobe and the Secrets of Puppetry

The Involuntary Sojourner: A Case Study

About the Author

About the Publisher

Ten Views of the Border

The imposition of borders was met, initially, with something akin to relief. This isn’t to say that the citizens of the region were pleased at the prospect of seeing their familiar world dismantled before their eyes, but the period leading up to the imposition had been, let us not forget, pestered by rumor and anxiety. Now at least matters had been decided, and there was a general hope on the part of both the Northwestern and Southeastern Inhabitants (strange to hear ourselves described this way!) that life would return to normal.

But what was normal now? The respective governments issued a joint statement: “Northwestern Inhabitants (hereafter NWI) and Southeastern Inhabitants (hereafter SEI) are encouraged to pursue ordinary daily activities subject to minor alterations in keeping with the new regulations as listed below.” No one read these regulations. Not at first. Or, rather, those who did found them a source of amusement, to be read aloud at dinner parties attended by NWI and SEI, still mingling freely, pointing and laughing at the colored bracelets as if they were part of a deliciously absurd new party game.

•••

Oskar Leong-Burke, born Year 2, NWI by birth, SEI by parentage, endured taunting with dignity from the earliest age. Secret pride, never acknowledged, may already have begun scraping out a cavity for itself by his shirttail-nibbling preschool days. Or his famous reserve might just as well have been a character trait utterly divorced from the events in his life. Try to sort these things out, try to trace bloom to root, and see how far you get. We know he never formally complained. No mention of his peculiar circumstances appears in his speeches, as if he found speaking of the matter beneath his dignity. (Again, dignity!) In any event, there was no need for him to mention those circumstances, as they were well known: the soon-to-be-father’s midnight rush to a Southeastern hospital; the pneumatic hiss of his wife’s breathing in the backseat. The necessary obstruction: either construction work or downed power line, depending on the version you favor. The rush in the opposite direction. The (ultimately venerated, initially reprimanded) border guard’s permission to cross. The hissing. The winding road. The Northwestern hospital. The moans. The confusion: Parent 1 and Parent 2? Southeastern Inhabitants. Birth location? Northwestern Administrative Region.

***

Obviously constructing a wall was impractical from the start. The general terrain of the region was not amenable. And the town itself—now the two towns—could hardly be split like a halved orange. The division, it was announced, should be conceived primarily as a state of mind. We were asked to regard the stripe across the town’s belly, garish as a new tattoo, the way we might a symbol. Whereas the gates on the main roads, the border patrols, the weapons—all of this we were encouraged to view as something other than symbolic.

The home of Willetta Clum-Edbril, bordering as it did the park and therefore a patch of land neither side was willing to relinquish, became a point of contention. Half of her home was now in the Northwestern Administrative Region, half in the Southeastern; but as she refused to consider relocation, in spite of reasonable offers from both governments, the new line was, in the end, painted up one wall, across the roof, and down the other wall. Dual citizenship having been disallowed, the question of Willetta Clum-Edbril’s status resulted in the determination that she would be awarded alternating citizenship: when in the Northwestern half of her home, she would be an NWI; when in the other half, an SEI. Since her front door offered egress to one region and her back door the other, it was only a matter of being certain to wear the appropriate bracelet before going out.

***

But I remember him coming in the border patrol truck every morning. Like they were bringing some famous criminal. Him getting out. Every day it was like it was his first day there. The look on his face, I mean. Creepy. I shouldn’t say that. But I mean. The teasing or bullying, I never took part in all that, but I can say, it sounds defensive or you know like apologizing or something for the behavior, but I don’t think it was because of his coming from the other side. That was just the excuse. It was the look on his face. I mean if he didn’t want to join in, then go play in a corner. Okay. Go play by yourself. But to just sit there at the edge of the playground and watch us all like that . . . Never a smile. It sounds like a blame-the-victim sort of, that kind of unfair sort of thing. But you didn’t see his face.

***

Each of the respective governments organized a contest to create an imagined history explaining the border for future generations. By a coincidence perhaps not so remarkable when you consider that we had, after all, until very recently been neighbors and fellow countrymen, both winning entries centered on the park.

The Northwestern entry reimagined it as the locus—the “historic heart,” to quote the essay—of Northwestern regional pride and identity. Southeastern usurpation of the park (described as thrillingly as a barbarian invasion in an adventure story) leads to the inevitable conflict which ends in the establishment of a borde

r. The other winning entry is as easily summarized: simply transpose in the above description the words “Northwestern” and “Southeastern.”

From what can be surmised, the park had in fact nothing to do with the reason for establishing the border (whatever that reason was), but it invoked, for citizens of both sides, memories of lazy leaf-shaded afternoons and picnics pleasantly disrupted by carousing off-leash dogs and fishing for nonexistent fish on the green-slimed steps of Muck Pond, so it was easy to convert this genuine nostalgia into a foundation upon which might be built the new history we were expected to pass on to our children.

***

But did little Oskar cry? No. He missed his father and mother just like you would, and the place called the relocation center was not a happy place, but little Oskar was brave. At night he looked out the window. And he thought of life on the other side of the border . . .

(In the accompanying black-and-white illustration, a barred oblong of moonlight stretches through darkness across a bare floor to an institutional cot, where it frames a boy, his tangled hair another patch of darkness. He is sitting up perfectly straight on the mattress, back and legs describing anatomically improbable right angles, staring toward the barred window although the look on his face is a listening look, as if he’s hearing something we can’t . . .)

***

As in a landmark? No, the park was never—

It was just a park. What do you want from a park?

Although we do have a landmark as a matter of fact. Nothing all that remarkable about it, though, I wouldn’t think.

Except that it’s the oldest barn in the region.

Battered but intact, you might say.

Yes, a monument to the old ways of building.

Or to traditional farm life.

Or to those things that bend and bow but manage to survive.

We don’t visit it much. After all, it’s a barn.

Although kids have been known to deface the walls.

Yes but otherwise it goes unnoticed by us for the most part.

***

There was at one point a TV program about Willetta Clum-Edbril. Really more about Willetta Clum-Edbril’s home, the inside of which was depicted as being bisected, like the outside, by a boundary line. A couch, a rug, the back of a perpetually sleeping Labrador: all were red-striped, and on either side of this stripe the ambience, the décor, even the pattern of the wallpaper were markedly different. Before crossing the line, the actress playing the part of Willetta Clum-Edbril would change bracelets, bathrobes, and slippers. This, one supposes, was meant to be funny. Naturally, none of us believed for a moment it was really anything like that. Those of us who actually knew her recall startled green eyes, the scent of fennel, and a fondness for hinges . . . In our imaginations, when we envision Willetta Clum-Edbril at home, we see her sweeping a floor unmarked by any dividing line. We have her cook palm fritters, a favorite local dish. We make her iron clothes. Ordinary things. Sometimes, in our imaginations, she is allowed to look through the window at the guarded and fenced-in park, but we require her to stay inside, where we need her; and if we do occasionally let her out we always make a point of looking away so we won’t know which door she is using.

***

The borderline as an Idea: it doesn’t do much for us. We don’t know what to do with it, this Idea. Those who endorse this view of the border make us feel slow-witted and literal. The fact is, for most of us, it’s a line. Broad and red and blistered in places. Two-dimensional but unquestionably real as it veers and rolls over three-dimensional space. Children play along the line on either side; some dare themselves to leap across and back again. (Although never little Oskar Leong-Burke!) The authorities, or at least those who actually monitor the borders, are surprisingly tolerant of this behavior. The line is an inconvenience. There’s the bakery with the cheese sticks you can no longer frequent. The shortcut turned long. Endless detours in fact. And of course the other part: the friends, the relatives, all of that. Work-related Day Visas have reportedly become harder to obtain. We curse the line openly. But we curse it as a painted line, not as an Idea. This is something we insist on.

***

The parade.

We march through the town, following the border, half of us on this side, half on that. The governments, although notified well in advance, have declined either to prohibit or to permit the parade, and this lack of recognition, this official silence, is interpreted variously by those among us as a sign of success or of failure. No one has gathered to watch; no crowds waving from the curb, no children hoisted onto shoulders. People look over, though, as they walk along the sidewalk. Their faces turn to observe from cars. A few lean out of windows. It wouldn’t necessarily be true to say that we are “regarded with suspicion.” Anyway, we are regarded; and the optimistic among us call it a sign of success. No one seems to recognize the man in the yellow poncho marching with us. It is a hot October afternoon, still summery, humidity gone now but the sun as bright and cruel as ever. At various points along the way we are forced temporarily apart, by buildings, walls, other assorted obstacles. We split apart and re-form again, following the line. What is the derivation of the term “Indian summer”? The question percolates, it effervesces up and down the processional line, but no answer is forthcoming. It wouldn’t necessarily be true to say that we are all completely satisfied with the parade thus far. Some of us might have expected more. From the parade? From ourselves? Some of us want to stop for a moment, to have a cool drink and to rest, even if that only means standing briefly in the gust of an air-conditioned doorway before resuming. This proposal is, ultimately, rejected. It is not possible to determine on which side of the line this rejection originated, or if it formed without respect to the line at all. We march on minus cool drinks, minus air-conditioning. There is no insurrection. The optimistic among us point to this as a sign of success. (The man in the yellow poncho reveals himself to be in the camp of the optimists.) We march on until we reach Willetta Clum-Edbril’s house. We have decided that this should be our end point. It really is unseasonably hot. We stand in front of Willetta Clum-Edbril’s house. Her curtains are drawn. Her hinges, a diverse collection dangling from eaves, windowsills, and shutters, creak in the breeze, the free flaps glinting and trembling like the wings of butterflies half-pinned to a board. Some of us observe for the first time that the borderline’s red stripe does actually, just as we have always heard, continue up the wall of her house; does actually cross the roof. Presumably does continue down the other side. Beyond, the park.

We stand there, the halted parade. We stand there for as long as we can, and then, in a collective decision that surprises us by its spontaneity, by not seeming like a decision at all, we turn silently around and we walk—we march, we march—back the way we came.

Maseru Casaba 9

The American boy was fifteen minutes late, and Kazu was starting to wonder if he’d gotten lost underground. From his car, Kazu scanned the heads that kept rising up out of Exit 4. Now and then blond appeared amid all the black, but each time it turned out to be another young Japanese with dyed hair.

It was his own fault: if he’d picked up his guest at the hotel, this would never have happened. Kazu had assumed that, since this was Jeremy’s second visit to Tokyo, he would be able to navigate the subway system on his own. But he should have known a boy like Jeremy would end up having trouble. A teenage sleight-of-hand prodigy, he’d come three years before to lecture to a group of Japanese magicians, although “lecture” was hardly the word for what transpired: he’d gazed down impersonally at his hands throughout, transfixed by the actions taking place there as if the hands belonged to someone else. He hadn’t even bothered to perform actual tricks; from start to finish, the show was an unapologetic display of card technique. His mute focus had made Kazu’s job of interpreting nearly impossible. When prodded to explain a sleight, Jeremy would blink up at Kazu, t

hen shrug, mumbling a few words Kazu could barely understand. It hadn’t mattered, in the end: the audience was there to witness a phenomenon, not to pretend they could duplicate the wunderkind’s feats. Kazu had expected the adoring teenagers; what had surprised him was the number of older magicians present, laughing ruefully at this seventeen-year-old’s mastery of moves that had eluded them after decades of patient mirror practice.

But even if the audience had seemed satisfied with this dour pantomime, Kazu, standing there uselessly, had felt humiliated. He was used to having expectant faces turn his way as he deciphered the foreigner’s secrets for them. And that was one reason why he’d invited Jeremy to his home this time: to coax some explanations from him in advance, so Kazu would be ready for the new lecture the following day.

But where was he? Kazu scanned the exit again: people trudged grimly up and out, up and out, refugees being steadily expelled from a subterranean kingdom. Still no sign of him. Could he have taken another exit by mistake?

Kazu was debating a call to Jeremy’s hotel when he spotted a yellow crown of ruffled hair—unmistakable this time—followed by the same narrow, sharply beaked face Kazu remembered from three years before. The expression there, though, seemed somehow different . . .

Kazu jumped out of the car. “Jeremy-san!” he cried, waving. “Over here!” (Kazu always added san after a name when speaking in English. During his year in the United States, there had been nothing more shameful to him than the sight of people from his country desperately aping the crude slang and backslapping jocularity they saw as typically American. He learned that Americans insisted on using given names—his magic mentor would repeat, almost angrily, “Call me Robert!” every time Kazu said “Mr. Ormea”—but he’d found himself unable to speak to those he respected without some sort of proper honorific, so he’d taken to adding san. He realized how strange it sounded, but he also noticed that people were charmed and amused by the exotic appellation; it confirmed, together with Kazu’s nervous deference, their image of what Japanese ought to be like, and over the years it had become a trademark, part of a character played for his foreign guests when they came to Japan.)

The Involuntary Sojourner

The Involuntary Sojourner